1. Introduction

The following report looks at several aspects of iron ore transportation worldwide, focusing on the Commonwealth of Australia (Australia) and the People’s Republic of China (China). Australia and China developed an important trade relationship over decades and centuries. China economic growth in the last decades, had a significant impact on the mining, production and shipping industry. Although the market and trade partnerships between the nations listed expanded over the last years, it is expected that the iron ore consumption of China will decrease in the future. Regardless, Australia is increasing its production and developing new infrastructure and technology to serve other markets. The study will illustrate the potential trade, in a suitable distinct approach to forecast outlooks, based on thorough findings of various data from the recent decade (2009–2019).

2. Material Overview

Iron ore is a popular construction material because of its affordable cost and excellent tensile strength, that why it is used in buildings, infrastructure, ships, and other applications as the predominant steel component. The four-digit commodity code 2601 of the global database’s standardised system specifies iron ores and concentrates, including roasted iron pyrites. Iron ore appears in 5% of the earth’s crust. Steel is similar to iron besides for the absence of carbon. Because other contaminants like silica, phosphorus, and sulphur significantly weaken steel, it is heated to roughly 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit (871 degrees Celsius). When iron ore is heated up, the contaminants, like carbon, oxidise and float away. Steel is made from 98 per cent of all iron ore mined. Steel accounts for 95% of all manufactured objects and is made from 98 per cent of all iron ore mining. (Nag, 2017)

3. Part 1 – Trade Portfolio

3.1 International Trade

The following chart shows the Iron Ore Price in US$ per tonnes from 2009 to 2021. The following section that follows explains and interprets the chart.

Source: https://www.marketindex.com.au/iron-ore

Global iron ore prices are unpredictable; the volatility from 2009 to 2019 is noteworthy. The price per dry metric ton unit at the beginning of 2009 was US$ 73.40, and by April of the year 2010, the price increased to US$ 172.90. After that, the cost of iron ore had a significant drop to 136.3$ in July 2010. The price could recover and grow to US$ 182.80 by February 2011. The following month the price of iron ore went into a slight dip and ended up at US$ 166.80 in June 2011. The cost of US$ 179.90 in August 2011 could not break above the all-time-high of US$ 185.60 (Jan 2011), which then indicated a new price trend. The dip in the price decreased the price of iron ore to US$ 118.40 by October 2011. The following month the price recovered but could not break above US$ 147.60 by March 2012. In July 2012, the price was again at US$ 117.00 but could not hold this price and went down to US$ 89.40$ by August 2012. Market participants exploited that opportunity to buy iron ore at a discount price; with that, the price went up again, and by January 2013, the price was at its highest price in a long time, which was US$ 152.50$. After that, the price dipped to US$ 110.40 by May 2013 and increased again until August 2013 to US$ 137.70.

When visualising the mentioned prices above on a chart, it is possible to draw a trend pattern called the head and shoulders pattern. The head and shoulder pattern either indicate a breakout or trend reversal; in the case of iron ore price, there was a decrease in the price until a value of US$ 41.50 in January 2016. From January 2016, the iron ore price developed a new trend with lots of higher highs and lower lows. In February 2017, the Iron Ore Price increased to US$ 91.20, just to have a drop after that in March 2017 to US$ 57.80. If we were generous, we could see an ascending triangle in the charts after that, which indicated a new upward trend and a price increase.

In July 2019, the price was at its highest high for a long time, which was US$ 115.55. At the end of the year 2019, the price was US$ 90.92. In the following period, the price changed more significantly and grew from US$ 81.35 in January 2020, up to a new all-time high of US$ 211.99 by July 2021. Unfortunately, the new all-time high did not last long, and the price dumped back to US$ 94.97 by November 2021. It would also be fascinating to analyse the years after 2019; unfortunately, most official websites do not provide data after 2019 yet. (Market Index, 2014b)

3.2 Market Sizes of choses countries

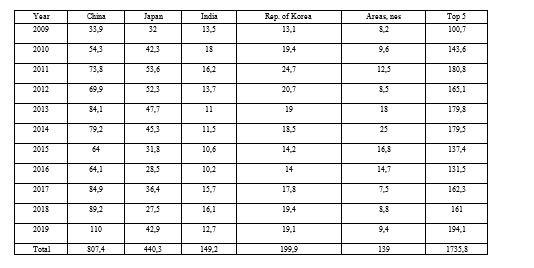

Australia has 5 top trading country partners and regions: China, Japan, India, Republic of Korea, and other countries of the region Areas, nes. Between 2009 and 2019, Australia’s top 5 trading partners had an average market share of 75 per cent of the total value. In the decade (2009 – 2019), China was the leading trading partner of Australia with a total of US$ 807.4 bn value traded, followed by Japan with US$ 440.3 bn, the Republic of Korea with US$ 199.9 bn, India with US$ 149.2 bn and Areas, nes with US$ 139 bn. From 2009 to 2019, the total trade value increased by 72.66 per cent. At the same time, the trade value with the top 5 partners only grew by 11.63 per cent. The fastest-growing trading relationship with Australia during the first half of the decade (2009 – 2014) had China, Hong Kong SAR (29 per cent), Areas, nes (24 per cent), Malaysia (23 per cent), Vietnam (22 per cent) and China (18 per cent), the fastest declining trading relationship with Australia had Italy (-5.7 per cent), India (-3,1 per cent), United Kingdom (-1,2 per cent). In the second half of the decade (2014 – 2019), the fastest-growing trade relationships had Philippines (12 per cent), Vietnam (12 per cent), Other Asia, nes (8,2 per cent), Chile (6.7 per cent) and India (2 per cent). Conversely, the fastest declining trade relationship had Australia with the Areas, nes (-81 per cent), China, Hong Kong SAR (-14 per cent), United Kingdom (-6.6 per cent), Thailand (6.5 per cent) and Bunkers (-6.1 per cent). (Resource Trade, 2019)

The following chart describes the Annual Trade Value of Australia in US$ over the decade (2009 – 2019). The three bars visualise the annual values of exports, imports and re-imports.

Source: https://comtrade.un.org/data/

By analysing the chart, it is possible to observe that the values of the re-import are significantly smaller as both the Import Value and the Export Value; with that, we can dismiss the re-import for our interpretation of the chart. From 2009 until 2016, the trade value of Imports and Exports did not change significantly compared to the years 2017, 2018 and 2019. Between 2016 and 2017, the trade value of the Exports grew by 142.76 per cent, and the Imports grew in the same period by 141.58 per cent. The following year (2018), the exports increased by 9.81 per cent compared to the previous year (2017), and the Imports increased by 2.95 per cent. After that, the exports grew by 5.39 per cent, and the Imports decreased by -5.97 per cent between 2018 and 2019. It could be assumed by the significant increase in traded value that Australia had an economic upswing. However, in December 2019, a new Virus (Covid-19) broke out, which had an economic impact on almost every country in the world. There are no data for 2020 and 2021, and no precise analytic results are possible. (Resource Trade, 2019)

3.3. Six Most Important Products Sectors

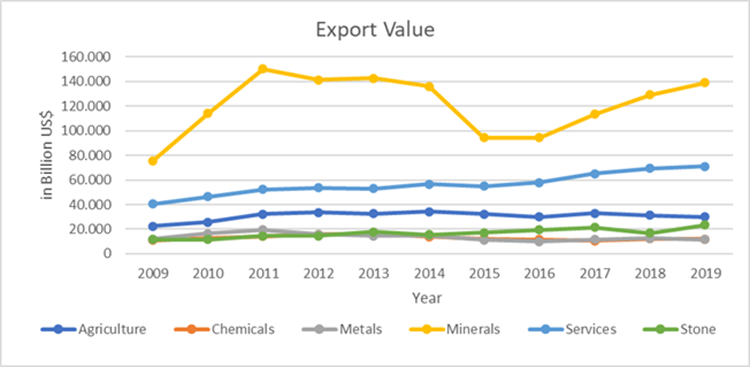

Australia has six major product sectors: Minerals, Services, Agriculture, Stone, Metals, and Chemicals. The mineral product sector is by far the biggest; this sector includes mineral products such as Iron ores and concentrates, Coal, Petroleum gases, Petroleum oils, crude, Copper ore. This sector is the biggest and will be discussed more in detail after summarising the other product sectors. The second-largest industry in the service sector includes Travel and Tourism, Transport, Information and Communications technology, insurance, and finance. The third most crucial product sector from Australia is the agriculture sector or, more specifically, the livestock production, which includes frozen Beef and lamb. The array of agriculture products includes but is not limited to the following products: Wheat and meslin, wine, bovine and fuelwood. The fourth biggest sector is stones, which include precious stones/metals and minerals contained in stones. Gold is by far the most significant imported product from the stone sector, and the second product is diamonds, the third jewellery of precious metal and the fourth silver. To the category metal belong products such as unwrought aluminium, refined copper and copper alloys, nickel unwrought, unwrought zinc, ferrous waste and scrap, lead refined unwrought and nickel powders. Australian chemical exports in 2019 also include the following: Aluminium oxide, medicaments, packaged, serums and vaccines (most likely due to Covid-19), make-up preparations, other colouring matter, uranium and vitamins. The following graph shows Australia’s export value in billion US$ from 2009 until 2019 of the top six export sectors, with which Australia produces the most significant annual revenue. (Resource Trade, 2019)

Source: https://comtrade.un.org/data/

The graph visualises that the mineral product sector is by far the most significant contributor to the Australian export value creation; with that a driving force of the Australian economy, because of that the following paragraph will give a summary of the Australian Mineral Sector during the past decade (2009 -2019), as well as a straightforward interpretation of the provided data. At the beginning of the decade, coal was the primary product with a gross export of US$ 29.8B, followed by iron ores and concentrates with US$ 22.2B. Iron ores and concentrates were followed by petroleum gases, petroleum oils, crude and copper ore. At the end of the decade, iron ores and concentrate exports had a gross export value of US$ 56.3 bn surpassed coal exports, which had a gross export value of US$ 38.7 bn. In 2009 petroleum gases had a traded export value of US$ 9.43 bn compared to the gross export value of petroleum oils, crude with US$ 5.21 bn. A decade later, in 2019, petroleum gases increased to a gross export value of US$ 26.5 bn and petroleum oils- & crude had a decrease to a gross export of US$ 3.91 bn. Copper ore export, which can also be considered an essential mineral, had a grown gross export value from US$ 2.52 bn to US$ 3.55 bn. (Un.org, 2019)

3.4 Geographical Distribution and Trading Routes

Seaborne trade accounts for over 90 per cent of Australia’s exports. Australia’s shipping sector is the world’s sixth largest, with bulk commodities exports being its principal export. Since bulk commodities dominate Australian exports, most Australian ports can handle the world’s largest bulk vessels. For example, iron ore, primarily mined in Western Australia, is the most commonly exported dry bulk commodity (in the Pilbara region and other parts of Australia and Tasmania). Because iron ore is a low-cost commodity compared to other commodities, shipping it by sea is the only viable option. In addition, the industry employs scale economics to make the iron ore trade more cost-effective. For example, the distance between the Port Hedland and Port of Qingdao is 4059nm, and a vessel travelling 13 knots would take 13 days for the voyage. (Ports.com, n.d.)

3.5 Evolution of Trade between the chosen countries

The market index stated that “Iron Ore is not traded like most commodities. The Market Index tracks the industry standard NYMEX traded 62 per cent Fe, CFR (Cost and Freight) China in US$/metric tonnes. China is one of the most prominent players in Iron Ore and the metal sector. Global economic growth is the primary factor in growing global iron ore demand. When the economy grows, the demand for steel increases, directly impacting the iron ore price. Since China is the biggest consumer of metals, the growth in China has a direct effect on the spot price of iron ore, and one can consider the spot price to be directly related to Chinese economic health.

Further, the market index explained that global economic growth is the primary factor that drives the supply and demand of iron ore; since China is one of the fastest-growing countries, it is clear why it stated CFR China in US$/metric tonnes. The abbreviation “CFR China” means the purchase price includes delivery to a specific port in China. (Market Index, 2014b)

The World Steel Association considers China to be the number one iron ore producer and the world’s largest consumer of iron ore. China needs Iron Ore for its steel industry, driven by its booming economy and the export of steel products. Since China’s domestic iron ore does not meet its consumer demand, China has to import Iron Ore from other Countries, such as Australia. (Ou, 2012). Between 2009 and 2019, China imported roughly 62 per cent of iron ore exports worldwide. During that period, the main trading partners of China were Australia, Brazil, South Africa and India. In the named period, China had the market dominance in these countries, to be exact between 80 per cent to 90 per cent, again with that kind of dominance, it is clear why they market index CFR China in US$/metric tonnes. The market index is called that way since China was and is the world’s largest iron ore importer and can drive the Cost and Freight Rate (CFR) and the price of iron ore per ton in the spot market. The market index says the following to that, “The iron ore spot price became a mature benchmark in 2008 when Platts started publishing daily assessments. The Steel Index and Metal Bulletin followed suit shortly afterwards. The industry-standard specification is 62% Fe (CFR China).” (Market Index, 2014b)

After 2009, China broke above the 60 per cent mark of the worldwide Iron Ore Imports. However, in 2010, Chinese iron ore imports decreased for seven months until October of the same year. In the same year, three raw material groups signed a contract concerning the international raw material price negotiation; from this point forward, the price was no longer negotiated annually, but rather on a quarterly basis. Between 2011 and 2012, however, the market peaked. Consequently, the freight rates increased rapidly, resulting in a reduced profit for Australia and other exporting nations. In 2015, the Australian Federal Department of Industry and Science had cut its price forecast for iron ore 2015 by 10 per cent, stating that China’s steel sector had a weak outlook. However, due to the reduced price, the Chinese demand soared again. At the same time, Australia could reduce competition and sell more of its product for a lower price. According to WITS, Australia could boost iron ore shipping because of the price reduction and had a loss in GDP in that year. (World Bank)

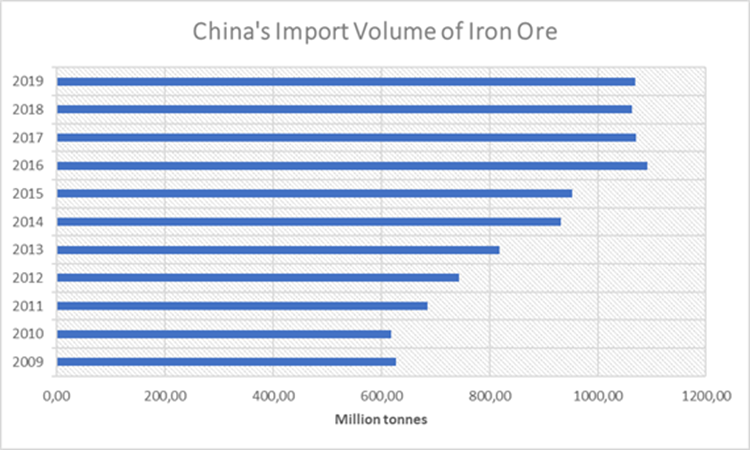

China’s Import Volume of Iron Ore:

The following bar diagram visualised China’s Import Volume of Iron Ore between 2009 and 2019.

Source: https://comtrade.un.org/data/

From 2009 until 2019, China accounted for an average of 62 per cent of global iron ore imports. To prove this case with an official source following citation from the publication “Western Australia Iron Ore Profile” from February 2019, which was published by the Government of Western Australia Department of Jobs, Tourism, Science and Innovation, can be taken into consideration “China accounted for 59% of global iron ore demand in 2018, followed by India (7%), Japan (6%), Russia (4%) and South Korea (4%).” (WA.gov.au, 2019). The following diagram shows the named figures. In 2009, China imported 627 m tonnes. Due to a lack of potential steel buyers, Chine decreased its iron ore import to 618 m tonnes the following year. After the difficulties from China to find suitable clientele for their steel products, they could increase their import significantly in 2010 to a sum of 685 m tonnes. In the following two years, the volume increased to 743 m tonnes in 2012 and 819 m tonnes in 2013. China could increase its import volume and break above the one bn tonnes mark by 2016 with 1.09 bn tonnes. The number of one billion tonnes of imported iron ore was also not broken in 2017, with a decrease China reached 1.071 bn tonnes of imports. In 2018, China’s Iron Ore Import Volume was still at 1.064 bn tonnes. This decrease in imports volume, which started in 2017, occurred because of the steel mills’ increase in scrap charges.

The report ‘China’s 2018 iron ore imports fall: Correction’ from the Argust Media group’ could make it possible to conclude plausible reasons for the drop in iron ore imports to China: “The country’s dependence on imports continues to increase amid environmental restrictions on domestic mines. Nevertheless, steel mills have increased their scrap charge in the converter burden since 2017, which may have marginally slowed the growth of iron ore imports.” (argusmedia.com, 2020). Despite the soaring iron ore futures price to almost 140 per cent, the world’s top steel producer, China, brought 1.069 bn tonnes of iron ore in 2019. The price of iron ore increased due to the increased sourcing of iron ore from smaller non-mainstream suppliers when a tailings dam at a Brazilian mine collapsed and a tropical cyclone was hit miners in Western Australia. The iron ore imports to the second highest ever in 2019. (Zhang and Daly, 2020) Australia: The trade between China and Australia is the most interesting in the iron ore sector since Australia has approximated 28 per cent of the world’s Economic Demonstrated Resources (EDR) and is ranked first in the world and the biggest iron ore supplier for China. Further, Australia is not only the most significant exporter but also the biggest producer of iron ore. (Market Index, 2014a)

Major global iron ore suppliers 2018: According to the Department of Jobs, Tourism, Science and Innovation of the Government of Western Australia, Western Australia was the largest iron ore supplier in the world and accounted for 39 per cent of global supply, in 2018. The second largest was Brazil, with 19 per cent of the worldwide supply. China, India and Russia are also significant iron ore suppliers, but they use most iron ore for their local steel production. In 2018, China accounted for 59 per cent of the global iron ore demand. (WA.gov.au, 2019)

Estimated iron ore resources in Australia: Again, taken from the Department of Jobs, Tourism, Science and Innovation of the Government of Western Australia, Western Australia had 29 per cent of the world’s iron ore reserves, which can be considered the largest in the world. Between 2017-2018 Western Australia has had enough economic demonstrated iron ore resources to withstand the current production for 60 days. The quality of the Australian iron ore reserves is by far not the best; in 2017, they contained 48 per cent, compared to the world average of 49 per cent and Brazil’s with 52 per cent, which is quite significant. Again, the iron ore production of Western Australia had an iron ore content of 62 per cent, which was again below the world average of 63 per cent and Brazil’s 64.2 per cent. (WA.gov.au, 2019)

China’s iron ore demand: Due to China’s growing economy, they needed more steel for export and their economy. Since iron ore is required to produce metals such as steel and the high production in China of named product, the price of iron ore went from US$ 28 a tonne between 1999 and 2000 to US$ 173 a tonne in 2007 to 2008. From 2008-09 to 2013-14, the iron ore price was US$ 129 a tonne. Consequently, to the slowdown in China’s demand, the exporting countries responded by reducing their supply, which led to an iron ore price decrease of 42 per cent in 2014-15 and again a decrease of 2014-15 of 28 per cent. As China’s iron ore demand increased in 2016-17, the price increased by 35 per cent to US$ 70 a tonne. The forecast from Australia for the year 2018-19 was an iron ore price of US$ 66 a tonne; in reality, the price was US$ 68.5. However, according to the Argus media, China’s iron ore imports fell by around 1pc in 2018, the second time annual imports have fallen compared with a year earlier this century. Further, the news stated that “January-December imports were 1.06 bn t compared with 1.07bn t the previous year, according to customs data. The last time iron ore imports fell was in 2010.”. (www.argusmedia.com, 2019). The 2019-20 forecast was at US$ 62 a tonne of iron ore, but the price reached US$ 92.6 a tonne, which was quite a significant difference. (WA.gov.au, 2019)

Total cash cost of seaborne iron ore exports in 2018: Even though the content of iron ore in the Australian product is lower than the average, the trade between them and China is still the most common since Australia and China are closer to each other than China and Brazil. Since the distance between Australia and Asia is shorter than between Brazil and China, the seaborne iron ore exports from Australia to Asia are among the world’s lowest, making trading with Australian iron ore miners very lucrative for China. For example, the average total cash cost was US$ 31.5 a tonne in 2018, whereas the world average was at US$ 31.9 a tonne during the same period. Due to the geographical location of Western Australia, the shipping costs to the largest iron ore market (Asia) are lower than that of the competition. A good example is the average iron ore shipping spot rate to North China; for Australia, this number increased 14 per cent (US$7.6), whereby Brazil’s rate went to US$ 18.5 a tonne. Since Australia and Brazil’s distance and price differences are significant, Australia and China are powerful economic partners. (WA.gov.au, 2019)

Major iron ore export markets: Apart from China, Western Australia’s iron ore industry has solid partnerships with other Asian countries. However, over 81 per cent (674 m tonnes) of Western Australia’s iron ore exports went to China in 2018. Australia was also responsible for 63 per cent of China’s iron ore imports during that year. (WA.gov.au, 2019)

Western Australian economic dependence on iron ore exports: Iron ore fines are by far the most significant contributor to the Western Australian production, the most produced product was iron ore fines (72 per cent), second lump (25 per cent), and concentrate as a third (3 per cent). With this distribution, it should already be clear that iron ore is an essential product in Australia and contributes a large part to the Western Australian economy. The iron ore industry accounted for 17 per cent of gross state product and 57 per cent of the mining industry of added value to the economy of Western Australia only in 2017-2018. In the same period, iron ore was with 47 per cent of merchandise exports by far the most exported merchandise of Western Australia’s exports. It made up 54 per cent of Western Australia’s minerals and petroleum sales. Iron ore also generated 77 per cent of Western Australia’s royalties in 2017-18 and 15 per cent of Western Australia’s government revenue in 2017-18. Iron ore production also plays a significant role in the generation of direct employment in the minerals mining industry in Western Australia. Direct employment in iron ore production has risen from 29 per cent in 2007-08 to 48 per cent in 2017-18. (WA.gov.au, 2019)

China’s Imports in US$ between 2009 and 2019: The following table show China’s sum of the iron ore trade volume with the world, as well Australia in US$ between 2009 and 2019 and the percentage of the share of Australia to the world stake.

Source: https://comtrade.un.org/data/

From 2009 with 40.5 per cent to 2012, Australia had a share of the world trade under 50 per cent. In 2013, Australia’s stake went over 50 per cent the first time. After that, it never went back under 50 per cent. Since 2015, Australia slice has gone over 60 per cent of the world iron ore trade with China. The period finished in 2019 with 60.22 per cent. Between 2009 and 2019, Australia’s share had an average of 55 per cent. (Un.org, 2019)

3.6 Conclusion

The data shows that Australia is the biggest iron ore producer and exporter, and China is the biggest iron ore importer and consumer, but that is not all. It can be assumed that China does not simply want to import iron ore and export steel products; they have bigger plans than that. Suppose believing Michael Pillsbury, who wrote the book “The Hundred-year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower”, China wants to be a global superpower like the USA. In that case, Chinas grand plan is to take over the world as the number one superpower, and they will not do that by just importing iron ore and producing steel products for other countries. (Mauldin, 2019) They need steel products first and foremost for their growing economy and to grow bigger. One of the most important factors to have a growing economy is to have sufficient infrastructure in place, and they need lots of iron ore and steel to construct that infrastructure. They are in this position that the index is called CFR China, and they can influence the global iron ore price. The iron ore market is a typical consumer market, where the consumer has the most power over the price. On the other hand, Australia is just like another country or continent; it is a continent where China can get cheap resources. Right now, Australia depends on China in multiple ways. Iron ore in Australia does not just represent another ordinary resource; it is the resource that contributes most to the revenue of Western Australia. Iron ore also impacts Australia economically, since the mining industry is a significant employer in Western Australia. Australia needs to diversify their product range because right now, its biggest export markets are travel and tourism and commodities such as iron ore, coal, petroleum gases and gold. (atlas.cid.harvard.edu, n.d.). In 2020, 41 per cent of goods went to China, and primary goods accounted for more than 80 per cent of that. Further, Australia lacks complexity in their exports, since in 2020, 98 per cent of primary goods exports were unprocessed. (Professor Laurenceson, 2021) The product sectors, which Australia has, are also not the best. Starting from the Covid-19 pandemic, travel and tourism is not the most profitable business. In the iron ore industry, they are subordinate to China. Coal and petroleum gases are also no future products, and gold reserves are also used up at some point. To sum up, China is on its way to becoming the new superpower. On the other hand, Australia has to find a way to diversify its exports, so they have a more complex range of products in the future and are not exposed to the risk of just having one major trading partner.

4. Part 2 The chosen product’s Industry

4.1 External Factors

Many factors influence the trade of iron ore between Australia and China. The biggest one yet happened around one and a half years ago caused by the pandemic, as diplomatic relations between the two countries fell to the ground. Australia’s prime minister Scott Morrison demanded an independent investigation into the origins of the Covid-19 outburst, tracing it back to the story of the Beijing outbreak. The Chinese government backfired by calling Morisson’s request a political manipulation, and therefore the Australian exports to China have been up against enormous difficulties. As export from Australia to China became much more complex, many deliveries never made it, sinking 62 per cent of Chinese investments in Australia. (Westcott, 2021)

4.1.1 Culture

As known, Australia is the largest producer of iron ore, mining more than 910 m metric tonnes in the 2019-2020 financial year, which is twice as much as Brazil, which is the second-largest producer. Most of that iron ore is exported to China as it is an essential element in steel production. China is the number one producer of steel as they have surpassed 1 bn tonnes a year. About 1.5 tonnes of iron ore are required to produce 1 ton of steel. China and Australia have helped grow their economies promptly these past two decades due to raw resources, especially iron ore. (Peach, 2021)

4.1.2 Infrastructure and Facilities

As Australia exports most of its iron ore to China, China uses that iron ore to create steel. About 1.5 tonnes of iron ore are required to produce 1 ton of steel. The iron ore imports of China increased by 9.5 per cent to the previous year. It has been used to help with infrastructures worldwide for the most significant economic crisis in the past years, the Covid-19 pandemic. Those infrastructures come up to US$ 500 bn, with Beijing’s need for steel never being higher. With that steel, infrastructures such as bridges, roads, commercial and residential buildings. Also worth mentioning, steel is necessary for ensuring energy infrastructure like wind turbines. Steel is mostly used in households, due to steel being an essential element for ovens, washing machines, fridges and dishwashers. (Australian Government Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, n.d.)

4.1.2.1 Australia’s Iron Ore Mining Companies

In the following, we will take a closer look at three of the largest iron ore mining companies located in Australia: Rio Tinto PLC, BHP Billiton Ltd. and Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. These companies operate and share large areas to mine iron ore. Each uses different technological innovations to ensure smooth, efficient production and subsequent shipping. All are future-oriented and move with the times. Therefore, technological progress is a top priority in every portfolio of each company

4.1.2.1.1 Rio Tinto Plc

Rio Tinto PLC is known as one of the largest mining companies in Western Australia. Due to the future, Rio Tinto is constantly investing to grow in the iron ore trade. Most of these investments are related to areas in Western Australia. One of these areas is Pilbara. Rio Tinto owns 16 mines and a 1.700 km railroad, which operates automatically through an autonomous system. This leads to an iron ore mining amount of one million tonnes per day, thereby Rio Tinto makes versatile investments in iron ore mining. Another technological innovation has begun in Gudai- Darri. 2.6 bn have already been invested, and all futuristic technologies will participate in this project. The location is expected to reach total capacity in 2023 (www.riotinto.com, n.d.). According to the financial statements of Rio Tinto PLC, production in the iron ore mining sector amounted to 345mt in 2021. As of 2020, the amount of production was 3 per cent lower. Looking at predictions, Rio Tinto PLC estimates the amount of iron ore mining in 2022 to be 350-355mt. (www.riotinto.com, 2021)

4.1.2.1.2 BHP Billiton Ltd

Together with Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton Ltd. is one of Australia’s largest iron ore miners. The company has long-term projects related to the environment. A primary goal is to reduce the emissions generated during the mining process to zero. For the implementation, 2050 is targeted, which initially seems distant but is worth its effectiveness. (Bhp.com, 2021) The economic situation of this company is excellent in the field of iron ore mining. Even during the pandemic, it was possible to increase the revenue from 20.797 m in 2020 to 34.475 m in 2021, which was an increase of 13.678 m (Dr Ellis and Bao, 2021). The total iron ore production amounted from 248mt in 2020 to 254mt in 2021; this leads to another guidance in iron ore production in 2022. According to forecasts, the amount of production in 2022 is estimated at 278-288mt (Bhp.com, 2021b).

4.1.2.1.3 Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (FMG)

Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. is also one of the largest mining companies operating in Australia. The company mines in the western area of Australia. Some of these areas are Chichester, Solomon and also Pilbara. (Wilson, 2021) All locations are connected to the Port of Hedland through a rail network, ensuring a smooth shipment to the customers. Since 2012, Fortescue has used the autonomous haulage system (AHS) on Caterpillar (CAT), which moves automatically (www.fmgl.com.au, n.d.). Fortescue MG is not afraid of the future. Projects are already underway to keep pace with the changing times. The guidance in iron ore shipment, the company predicts for 2022 is 180-185mt (www.fmgl.com.au, n.d.).

4.1.2.2 Australian Ports For Iron Ore

When it comes to iron ore shipment, there are three primary locations in Australia: Port Hedland, Port Dampier and Port Cape Lambert. The largest one of these is Port Hedland. Port Hedland is located on the North Coast of the Western Region and is the largest bulk export port with Pilbara Ports Authority. Three of Australia’s most prominent companies, Pilbara, BHP and Fortescue, operate mainly at this port. A record of half a billion tonnes was recorded here in one year, making it the largest port in the world. Another notable feature is a 400km railway connected to the mines of BHP and Fortescue. These transport the mined material directly for immediate loading and shipping. Due to statistics, Port of Headland is responsible for 57 per cent of iron ore export in Western Australia. With an export value of 22 per cent, Port Cape Lambert follows, which is also known as Port Walcott. This port is separated into two main terminals A and B, connected with the mining station Pilbara. Since Rio Tinto PLC expanded in Cape Lambert, the stats for this port have risen enormously. So, the leading company which operates here raised the annual capacity from 150mt to 210mt. Rio Tinto is responsible for 53 per cent of the iron ore shipments from this port. Finally, Australia has the Port of Dampier. The port is located on the North Coast of Australia in the Dampier Archipelago. In addition to iron ore shipments, other services in bulk liquid, LNG and general cargo are in service. The peculiarity at this port is a sensitive environment with a marine park. Under Pilbara Ports, authority new figures and stats for 2021 arrived. So, the total delivered throughput was 15.9mt in December 2021. For FY21, the total delivery of 175mt of iron ore was recorded (Cholteeva, 2020).

4.1.2.2.1 China Iron Ore Import Companies

China is one of the top traders, consumers and producers of iron ore. The record total of iron ore produced in 2020 was 340 m tonnes, making China the fourth biggest iron ore producing country globally. In addition, there are an estimated 20 bn tonnes of crude iron ore reserves in China. These reserves feed their huge steelmaking industry. Nevertheless, this is not enough, so in the case of iron ore export and import, China is the top leading one. Again, we will take a closer look at three of the largest companies settled in China. These companies are Rui Guang Lian Group, Tianjin Material& Equipment Corp. and China Minmetals Corp (Zhu, 2015).

RGL is one of the largest iron ore traders based in Beijing. This company is privatised. RGL has managed to play a significant role in this industry through a shareholder position and various investments. One of the companies is the Mineral Bay Cooperation, an association of several companies investing in iron ore mining (Zhu, 2015).

Tianjin M&E, on the other hand, is a state-supported iron ore distribution company based in Tianjin. In addition to trading in iron ore, the company also operates on a large scale in energy production through coal, oil and gas.

Tewoo is one of China’s largest iron ore traders and has cooperative relationships with many mineral producers and traders such as BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Fortescue Metals Group (Australia) and Santa Fe Mining (Chile) (Zhu, 2015). Another company operating under state supervision is China Minmetals. The company was newly founded by the combination of two companies; the China Minmetals (CMM), which has existed since 1950, and the Metallurgical Corporation of China (MCC). The estimated turnover per year is about US$100 bn. They have 42 mines, including 15 overseas mines located in Asia, Oceania, South America, and Africa. China Minmetals invests heavily in steel projects where its iron ore finds efficient application. (www.minmetals.com, n.d.)

4.1.2.3 Chinese Ports for Iron Ore

According to steel information providers, 199 shiploads of 25mt of iron ore each were unloaded at 45 ports in China in just one month. One of these mega ports is Qingdao. This port is located in Shandong province, also known for its growing economy. Qingdao is indispensable as a route for international shipment. Thus, it invests billions annually to counteract technological progress.

The port of Qingdao is always actively exploring new trade modes of ore to provide a door-to-door service for its clients. Improvements include stowage and efficient loading and unloading capabilities.

China’s Tianjin Port recorded an increase of about 60 per cent in iron ore imports to around 57 m tonnes last year. The continued growth in iron ore imports is related to the enormous demand for raw materials from the country’s steel industry. (GT staff reporters, 2021)

4.1.3 Technological Developments

Although steel leads to a low-carbon economy, its production leads to 7 per cent of the global GHG emissions. Reducing those substantial emissions can be caused by optimizing recycled volumes and production processes. With companies representing 20 per cent of the worlds steel production setting net-zero targets, our planet has a bright future. Investing in a low-carbon future requires a strong business and policies that fully take global competition into account. The transition into a net-zero future will considerably impact low-cost and plentiful zero-carbon electricity, carbon capture and storage, also known as CCS, infrastructure and sequestration capacity as there will be more accessibility to these sectors. Natural gas, which is a transition fuel, will also be more accessible as it is competitively pricy. Therefore, greening the steel sector is critical for a low-carbon future. There is no way around steel as it is a significant factor in energy transition many technologies for decarbonisation. It is essential to reduce carbon emission as the steel sector is the most significant carbon emitter from the heavy industries that provide essential materials for modern life. (NET-ZERO STEEL SECTOR TRANSITION STRATEGY, 2021)

4.1.4 Policies and Regulations

The Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Reviews (STIP Reviews) undertaken by UNCTAD exists for STI stakeholders to understand better the critical strengths and weaknesses of their novelty systems and identify improvements when needed and policy options for their development in the future. The environment plays a considerable role in policies and regulations. That specific framework should be filled with motivation for established and emerging companies to develop their learning, knowledge and innovation skills and invest in learning. The STI policy should comply with various policies, such as industrial policies, policies on trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), education and training. (Sirimanne et al., 2019)

4.1.4.1 Legal Trade Agreement (ChAFTA)

According to international law, a free trade agreement (FTA) is an agreement between two or more parties. To reduce or even eliminate trade barriers, FTAs determine the tariffs and duties that countries set on imports and exports, leading to economic growth. With a lower price comes increased access to goods with higher quality due to free trade. Not only does this positively affect the companies, but also the inhabitants. Once import costs are reduced or eliminated, production costs would also decrease, resulting in higher wages, as the profit increases, giving the company opportunities to make the employers happier. More opportunities are created as the company wants to grow; therefore, new job positions are created. The ChAFTA is the most important free trade agreement between China and Australia as it entered into force on the 20th of December 2015. This opened new paths for economic relations between China and Australia at the time. China is Australia’s biggest export market which created significant paths from the present to the future for goods and services due to China having one-third of Australia’s exports. (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2018)

Some steps need to be taken into consideration by Australian exporters and importers to have a specific advantage in preferential tariff treatment from the ChAFTA. Firstly, the tariff classification of each good has to be identified individually. The Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System, which is internationally recognised, the ChAFT uses to identify the goods. This classification system uses more than 5200 six-digit product categories for the goods. There are goods not included in this list as these are not comparable between countries. The next step that has to be considered is exporting or importing that particular product. Every good is being treated differently by the ChAFTA. Therefore, having the tariff code can be a determining factor. Once this has been considered, exporters and importers check if the product meets the rules of origin requirements. The rules of origin (ROO) are criteria that only products originating in China or Australia can benefit from the agreement. Therefore, importers and exporters have to know where their products originate from, otherwise the ChAFTA does not apply. To that, a certificate must be prepared to be preferred for tariff treatment according to the ChAFTA, with documents having to be demonstrated; this can be done by using ChAFTA’s certificate of origin (COO) or the declaration of origin (DOO). (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, n.d.)

4.1.5 Sustainability and Impact on the Environment

The mining of iron ore has a massive impact on the environment. Every year an estimated 2.000 m tonnes of iron ore are being mined, and the steel industry uses about 95 per cent of that amount. We pretty much cannot do anything that does not somehow require iron. Nevertheless, the environmental impact of iron is enormous. The production of iron requires much energy and causes air pollution in the form of nitrous oxide, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and sulphur dioxide from diesel generators, trucks and other equipment. Iron ore mining also causes water pollution of heavy metals and acid that drains from the mines. Acid drainage can go on for thousands of years after the mining activities have stopped. Steel requires about 20 gigajoules of energy per ton produced. Three-quarters of the energy comes from burning coal. Steel production also requires significant inputs of coke (a sort of coal) which is highly damaging to the environment. Coke ovens emit air pollution such as naphthalene, which is highly toxic and can cause cancer. On average, 1.83 tonnes of CO2 are emitted for every ton of steel produced, making steel production a significant contributor to global warming, adding over 3,3 m tonnes annually to global emissions. (Environmental Justice Australia, 2017)

4.1.6 Future Consumer Behaviour

The SMM News website reported that in 2021 the iron ore price rose while consumption grew slowly in the second half of the year. Further, they reported that the American credit rating agency Fitch Solutions stated in a report, “Iron ore and steel prices are rising again amid strong demand in China’s steel industry and supply problems for the world’s largest producers” (SMM compilation, 2021). The mentioned should also limit the iron ore gains in the following months due to the weakened consumption by the downstream companies. (SMM compilation, 2021)

Another report from the Zawya media website reported that China’s steel consumption would dip further in 2022 due to “policies for the real estate market and uncertainties linked to COVID-19 curb demand”. According to a government consultant, “Consumption in the construction sector, energy and containers […] will decrease slightly in 2022, but the steel demand for machinery, automobile, shipbuilding and home appliances will continue growing.”. The Chinese government also wants to start new infrastructure constructions to support the steel sector. However, the steel demand goes down, and more steel scrap is recycled, lowering the demand for iron ore. (Zhang and Patton, 2021)

In Western Australia, iron ore profile from February 2019 is reported that the AME Group forecast that China’s iron ore demand will fall gradually over the next 20 years to 1.071 m tonnes in 2038. (WA.gov.au, 2019)

4.1.6.1 Potential Trade

Iron ore is the world’s third most-produced commodity by volume – after crude oil and coal – and the second most traded commodity – only beaten by crude oil, with Australia being one of the leading producers, many countries, such as China, demand Australian iron ore, an essential component for their iron and steel industries.

4.1.7 Company Contracts and Joint Ventures

A temporary business relationship is used for two or more business parties or individuals, the so-called joint venture agreement, to achieve a common goal. There are two types of joint ventures. The contractual and the general partnership is being used when two or more businesses agree to collaborate on a business project that includes a signed agreement that they are working together under specific terms of the contract. Profits and/or losses are not being shared using this kind of contract, and the companies continue working on their own; the only difference here is that they all have the same goal. There are no registration requirements for any companies, and they keep the accounting records separately.

On the other hand, the general partnership is a joint venture where the parties share the profits and/or losses of the project. Joint ventures are formed when the joint parties want to achieve a common goal, sharing the risk and reward; this can help each business grow, independent of any outside funding. (www.lawdepot.com, n.d.)

4.2 Discussion of the impacts of Corona Crisis

The Mineral Commodity Summaries described the current situation very well, “Significant decreases in production, shipments, and trade in 2020 were due to the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which lowered steel production and consumption globally. […] Overall, global prices trended upwards to an average value of $97.96 per ton in the first eight months of 2020, a 4% increase from the 2019 annual average of $93.85 per ton and a 40% increase from the 2018 annual average of $69.75 per ton. Based on reported prices for iron ore fines (62% iron content) imported into China (cost and freight into Tianjin Port), the highest monthly average price during the first eight months of 2020 was $121.07 per ton in August compared with the high of $120.24 per ton in July 2019. The lowest monthly average price during the same period in 2020 was $84.73 per ton in April, compared with the low of $76.16 per ton in January 2019. The prices trended upwards due to a reduced supply of higher-grade iron ore products, spurred partially by the closures of pelletising plants in Brazil. One company in Brazil cut guidance for pellet sales in 2020 by 25 m to 30 m tonnes based on first-quarter projections following 302 m tonnes of iron ore production in 2019, a decrease from 385 m tonnes produced in 2018, owing to a tailings dam collapse that idled operations at the collocated mine. […] Globally, iron ore production in 2020 was expected to decrease slightly from 2019. Global finished steel consumption was forecast by the World Steel Association to decrease by 2.4% in 2020 and increase by 4.1% in 2021.” (MINERAL COMMODITY SUMMARIES 2021, 2021)

According to the bulletin, the mining industry faces other challenges post-Covid. The first challenge is that mining has a bad reputation for being a carbon-intensive, dirty and socially irresponsible industry. Society wants a cleaner, greener world, but they have to understand that the components, for example, solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles and smartphones, need to be mined in the first place. The new generation should also see the mining industry as a potential employer, where they could actively develop solutions rather than solely protesting against the industry. If the misconception about mining continues, it will also be challenging to secure external investments.

Further, the bulletin stated that the mining industry needs to adopt new mining technology: “The right technologies will reduce employees’ exposure to harsh working conditions, resulting in a safer working environment with fewer injuries and stoppages. Moreover, it can make the industry cleaner, greener, efficient, sustainable, and more profitable. […] mining will need to secure new capabilities in IT, automation and, perhaps more than anything, analytics.”. (Meldrum, 2021). Many young people are studying STEM academic disciplines; for them, mining could be a great way to transform a high-carbon industry into an efficient and sustainable industry. For example, the steelmaker ArcelorMittal in Bremen got an investment of 10 m euros from the city-state Bremen to transform their energy supply from coal to hydrogen. “The project includes the construction of a 12MW electrolysis plant.” (Bone, 2021).

Another problem is that when governments want more investment or royalties from the iron ore miners, the iron ore price will go up. With that, China will most likely start to look for more economically alternative iron ore and coal supplies. The mining industry also faces a diversity problem. First of which is that the mining industry employs not many women. Second, the mining industry has problems attracting the young generation, so most of the workforce is overaged. There is neurodiversity’s, for example, ADHD, dyslexia, and autism, which could benefit the mining industry in the form of new ideas and solutions. The individuals with those conditions could also benefit from this kind of work because they could earn a higher salary.

Last but not least, the mining industry has to start to employ people with other career paths than just the traditional background. People from other industries such as IT and automation could bring a valuable skillset into the industry. All these issues come down to one thing: the shortfall of talented employees; since a significant per cent of senior leaders are retiring, many emerging leaders face redundancies, and the younger generation seems to have a lack of interest in the mining industry. Therefore, the mining industry has to develop new solutions facing the challenges of digitalisation and improve its leadership and management styles (Meldrum, 2021). The mining industry could use the Covid-19 pandemic to introduce new technical solutions since now people are more willing to adapt.

4.3 Analysis

The Flows, such as Physical Flow and Actors, Information Flow, Financial Flows, are for the most part always going to be the same in the trading of commodities, and industry participants will be familiar with them. A single commodity company cannot influence external factors, cultural aspects, infrastructure and facilities, and technological developments. What is essential to be considered is the policies and regulations, if there are changes that could impact the trade and the profitability of the transaction. In the future, sustainability will also play a significant role in developing business plans and strategies for companies. Another big issue companies face nowadays is the Covid-19 crisis, which can have a vast impact in multiply ways. The impacts of the crisis could be the following: reduced production, reduced demand, the prolonged implementation time of the transaction, employees could be infected by the virus and stay away from work due to sickness. Many factors have to be considered, and when such trade takes place, it should be clear how they are going to be handled.

5. Conclusions

The main goal of a trading company is to make a profit through the delivery of a service, which is the supply of a commodity in a certain quantity, quality and time. China is the biggest importer, making a trade with them one of the most lucrative. Australia has the biggest iron ore reserve, and the delivery of iron ore from Australia to China is the cheapest. So, the primary conditions for suitable trading are in place. The company would support China’s growth with the trade is of minor importance because if they do not do it, someone else will. Marc Rich used to say: “I deliver a service. People want to sell oil to me, and other people want to buy oil from me. I am a businessman, not a politician.”. (Rankin, 2013) Marc Rich was not just a businessman; he was known to be

“The King of Oil” because he bought between 1979-81 oil from Iran during the oil embargo and sold it to Israel. Even though both parties knew who the other party was, nobody cared, nonetheless Marc Rich was convicted of trading with Iran during the oil embargo and combined with additional charges. The US wanted to sentence Marc Rich to more than 300 years. (Wikipedia Contributors, 2019)

With that said, when looking at the trade portfolio, which is the first part of the report, it is clear that the iron ore trade between China and Australia is already established and profitable for more than a decade. Since China want to be the global superpower by 2049, which is still 27 years away, the iron ore trade will continually be attractive. There might be some periods that could end up being more volatile. However, even these periods could be efficiently hedged with financial instruments like paper trading, options and futures. One way to make long-term profitable trade would be to make long-term contracts with a supplier, a buyer and a time charter agreement with a shipowner.

Even when considering the external factors, the trade would be desirable. The report showed external factors favouring the trade, such as the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement. Technical developments of the industry transform the mining sector into a more sustainable and carbon-efficient industry and make it more attractive for the younger generation, which puts enormous emphasis on the greening of industries. The mining industry is introducing new solutions and all players of the value chain, such as the shipping industry with LNG-ships and the steel mills with hydrogen power plants. These greening solutions make the trade even more lucrative since efficient production processes could reduce costs. Companies with more sustainable production processes could also get sustainability certificates and make their products more attractive for buyers, who put much value into sustainability. A solution from a trading company could be to develop a supply chain that puts an extra focus on sustainability; for example, they could work together with mining companies, shipowners and steel mills to develop solutions. Governments want to reduce climate change; they agreed on the Paris Agreement to handle the issue by supporting actions to reduce emissions and uphold and promote regional and international cooperation (European Commission, n.d.). Since this kind of cooperation would be in accordance with the Paris Agreement, the companies could try to secure investments from the involved governments.

6. Limitations and Future Research

There are limitations of the report since there was only data available until 2019; add to that, the Covid-19 crises that started around that time had a significant impact on the world economy, especially China. Therefore, the report only uses data to analyse the period pre-Covid. Further limitations were the lack of reported data from countries; for instance, the world exported more than it imported, which cannot be correct because this should correlate with each other. Another limitation lies in the contradictions of data from different sources; that does not mean one source is more valid, but it has to be clear how to handle such issues to do future research. For instance, it would be possible to use the data from multiple sources and analyse them to understand where these differences originate from.

References

atlas.cid.harvard.edu. (n.d.). The Atlas of Economic Complexity by @HarvardGrwthLab. [online] Available at: https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Australian Government Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications. (n.d.). SUPPORTING PAPER NO. 2 MARITIME FREIGHT. [online] Available at: https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/transport/freight/freight-supply-chain-priorities/supporting-papers/files/Supporting_Paper_No2_Maritime.pdf [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Bhp.com. (2021a). Annual reporting. [online] Available at: https://www.bhp.com/investors/annual-reporting [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Bhp.com. (2021b). Our future. [online] Available at: https://www.bhp.com/about/our-future [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Bone, C. (2021). ArcelorMittal Bremen’s joint hydrogen project gets state funding | Metal Bulletin.com. [online] www.metalbulletin.com. Available at: https://www.metalbulletin.com/Article/4021653/ArcelorMittal-Bremens-joint-hydrogen-project-gets-state-funding.html [Accessed 24 Jan. 2022].

Chen, J. (2019a). Learn About Trading FX with This Beginner’s Guide to Forex Trading. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/forex/11/why-trade-forex.asp [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Chen, J. (2019b). Option Definition. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/option.asp [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Chen, J. (2021). What Are Freight Derivatives? [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/freight_derivatives.asp [Accessed 31 Jan. 2022].

Cholteeva, Y. (2020). Mapping Australia’s mining ports. [online] www.mining-technology.com. Available at: https://www.mining-technology.com/features/mapping-australias-mining-ports/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2018). Australia’s free trade agreements (FTAs). [online] Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Available at: https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/trade-agreements [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (n.d.). China–Australia Free Trade Agreement | DFAT. [online] www.dfat.gov.au. Available at: https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/Pages/australia-china-fta [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Dr. Ellis, B. and Bao, W. (2021). Pathways to decarbonisation episode two: steelmaking technology. [online] bhp.com. Available at: https://www.bhp.com/news/prospects/2020/11/pathways-to-decarbonisation-episode-two-steelmaking-technology [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Environmental Justice Australia. (2017). Air pollution – Environmental Justice Australia. [online] Available at: https://www.envirojustice.org.au/our-work/community/air-pollution/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

European Commission (n.d.). Paris Agreement. [online] ec.europa.eu. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/international-action-climate-change/climate-negotiations/paris-agreement_en [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Fernando, J. (2019). How Futures Are Traded. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/futures.asp [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

GT staff reporters (2021). Iron ore backlog at Chinese ports intensifies – Global Times. [online] www.globaltimes.cn. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202108/1232251.shtml?id=11 [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Majaski, C. (2021). Paper Trade: Practice Trading Without the Risk of Losing Your Money. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/papertrade.asp [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Market Index (2014a). Australian Mineral Resources. [online] Market Index. Available at: https://www.marketindex.com.au/australian-mineral-resources [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Market Index. (2014b). Iron Ore. [online] Available at: https://www.marketindex.com.au/iron-ore [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Mauldin, J. (2019). China’s Grand Plan To Take Over The World. [online] Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnmauldin/2019/11/12/chinas-grand-plan-to-take-over-the-world/?sh=41f584165ab5 [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022]. Meldrum, L. (2021). Six critical challenges facing mining post-COVID. [online] bulletin. Available at: https://www.ausimm.com/bulletin/bulletin-articles/six-critical-challenges-facing-mining-post-covid/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

MINERAL COMMODITY SUMMARIES 2021. (2021). [online] USGS Publications Warehouse. U.S. Geological Survey Publications Warehouse. Available at: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021.pdf [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Nag, O.S. (2017). What is Iron Ore? [online] WorldAtlas. Available at: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/iron-ore-facts-geology-of-the-world.html [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

NET-ZERO STEEL SECTOR TRANSITION STRATEGY. (2021). [online] missionpossiblepartnership.org. Mission Possible Partnership. Available at: https://missionpossiblepartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/MPP-Steel_Transition-Strategy-Oct19-2021.pdf [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Noah, D. (2018). 8 Documents Required for International Shipping. [online] Shippingsolutions.com. Available at: https://www.shippingsolutions.com/blog/documents-required-for-international-shipping [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Ou, L. (2012). China’s Influence on the World’s Iron Ore Market A Supply-Side Perspective. [online] econ.berkeley.edu. Berkeley Economics University of California. Available at: https://www.econ.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/Thesis%20Paper_Lingxiao%20Ou.pdf [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Peach, B. (2021). Why iron ore is crucial in China’s infrastructure boom. [online] China Macro Economy. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3120761/how-iron-ore-powering-chinas-infrastructure-boom-and-why [Accessed 24 Jan. 2022].

Ports.com. (n.d.). Sea rout & distance. [online] Available at: http://ports.com/sea-route/port-of-shanghai,china/port-of-darwin,australia/#/?a=5&b=4614&c=Port%20Hedland,%20Australia&d=Port%20of%20Qingdao,%20China [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Professor Laurenceson, J. (2021). Australia’s export mix, industrial base and economic resilience challenge. [online] UTS ACRI. Available at: https://www.australiachinarelations.org/content/australias-export-mix-industrial-base-and-economic-resilience-challenge [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022]. Rankin, J. (2013). Marc Rich: controversial commodities trader and former fugitive dies aged 78. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jun/26/marc-rich-commodities-trader-fugitive-dies [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Resource Trade. (2019). Data. [online] Available at: https://resourcetrade.earth/?year=2019&exporter=36&importer=156&category=157&units=value&autozoom=1 [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Sirimanne, S.N., Bokor, K., Calovski, D., Sanz, A.G., Lim, M., Miedzinski, M. and Wu, D. (2019). Harnessing innovation for sustainable development. [online] unctad.org. UNCTAD: United Nations. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/dtlstict2019d4_en.pdf [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Small Business Team, Ex-Im Bank (2014). How Does A Letter of Credit Work and What Is It ? [online] grow.exim.gov. Available at: https://grow.exim.gov/blog/how-does-a-letter-of-credit-work-and-what-is-it [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

SMM compilation (2021). Iron ore prices rise while Fitch thinks consumption growth slows in the second half of the year_SMM | Shanghai Non ferrous Metals. [online] news.metal.com. Available at: https://news.metal.com/newscontent/101517514/Iron-ore-prices-rise-while-Fitch-thinks-consumption-growth-slows-in-the-second-half-of-the-year/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

U.S. Geological Survey (2019). Mineral Commodity Summaries | U.S. Geological Survey. [online] www.usgs.gov. Available at: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/mineral-commodity-summaries [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Un.org. (2019). International Trade Statistics. [online] Available at: https://comtrade.un.org/data/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

WA.gov.au. (2019). Western Australia Iron Ore Profile. [online] Available at: https://www.jtsi.wa.gov.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/wa-iron-ore-profile—february-2019.pdf?sfvrsn=3f38731c_4 [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Westcott, B. (2021). Analysis: Iron ore is saving Australia’s trade with China. How long can it last? [online] CNN Business. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/05/05/economy/australia-china-iron-ore-trade-intl-hnk/index.html [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Wikipedia Contributors (2019). Marc Rich. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marc_Rich [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022]. Wilson, C. (2021). December 2020 Quarterly Production Report. [online] fmgl.com.au. East Perth, Western Australia 6004: Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. Available at: https://www.fmgl.com.au/docs/default-source/announcements/september-2021-quarterly-production-report.pd [Accessed 27 Jan. 2022].

World Bank (n.d.). Australia Trade Summary 2015 | WITS | Text. [online] World Integrated Trade Solution. Available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/AUS/Year/2015/SummaryText [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

www.argusmedia.com. (2019). China’s 2018 iron ore imports fall: Correction | Argus Media. [online] Available at: https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news/1826857-chinas-2018-iron-ore-imports-fall-correction [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

www.fmgl.com.au. (n.d.). Our Operations | Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. [online] Available at: https://www.fmgl.com.au/about-fortescue/our-operations [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

www.fmgl.com.au. (n.d.). Results and Operational Performance | Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. [online] Available at: https://www.fmgl.com.au/investors/results-and-operational-performance [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

www.komgo.io. (n.d.). Komgo Home. [online] Available at: https://www.komgo.io/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

www.lawdepot.com. (n.d.). Joint Venture Agreement | Free Joint Venture Forms (US) | LawDepot. [online] Available at: https://www.lawdepot.com/contracts/joint-venture-agreement/?loc=US#.YesQAf7MJPY [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

www.minmetals.com. (n.d.). China Minmetals Corporation. [online] Available at: http://www.minmetals.com/english/about_666/AboutMinmetals/ [Accessed 27 Jan. 2022].

www.riotinto.com. (n.d.). Iron Ore. [online] Available at: https://www.riotinto.com/products/iron-ore [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

www.riotinto.com. (2021). Results. [online] Available at: https://www.riotinto.com/invest/financial-news-performance/results [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Ying, X. (2019). Brazil Loses its Share in Global Iron Ore Market. [online] The Rio Times. Available at: https://www.riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio-business/brazil-loses-its-share-in-global-iron-ore-market/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Zhang, M. and Daly, T. (2020). China’s 2019 iron ore imports rise to second-highest ever. Reuters. [online] 14 Jan. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-economy-trade-ironore-idUSKBN1ZD09H [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022]. Zhang, M. and Patton, D. (2021). China’s 2022 steel demand set to dip on property policy, pandemic. [online] www.zawya.com. Available at: https://www.zawya.com/uae/en/story/Chinas_2022_steel_demand_set_to_dip_on_property_policy_pandemic-TR20211215nL4N2T029AX1/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Zhu, S. (2015). FEATURE: Who are China’s top iron ore traders? | Metal Bulletin.com. [online] www.metalbulletin.com. Available at: https://www.metalbulletin.com/Article/3426878/FEATURE-Who-are-Chinas-top-iron-ore-traders.html [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Zhu, S. and Madsen, M. (2015). FEATURE: Who are China’s top iron ore traders? | Metal Bulletin.com. [online] www.metalbulletin.com. Available at: https://www.metalbulletin.com/Article/3426878/FEATURE-Who-are-Chinas-top-iron-ore-traders.html?ArticleId=3426878 [Accessed 23 Jan. 2022].

Appendix